Well, what does the evidence show?

As an atheist, one of my most firmly held beliefs was in the natural goodness of people, even if it was only a consequence of a materialistic evolutionary process.

It usually goes without saying that, in most of us at least, resides a fundamental belief in what it means to be – and to do – good, and that our natural instinct and tendency lies in that direction. After all, if you look at any civilised society, from an individual to an institutional level we see that:

-

the goal is to improve the lives of people,

-

the preference is for peace over war, and

-

the triumph of humanity would be a society where everyone is fundamentally happy.

Why is this?

1. We Have Empathy

This is our first example of a human trait that exists at the individual level, and that has a significant impact on society.

Most people – to a greater or admittedly sometimes lesser degree – will react instinctively to the plight of someone with whom they can identify.

In fact, anthropological studies have shown that this is a significant evolutionary advantage [1]. This is known as altruism, being a uniquely human feature where an individual takes committed action for the benefit of others, but with full awareness of a real cost to themselves.

And let’s face it, in most instances, most people do not wish harm on another person.

2. We are Optimists

Another trait that most people possess naturally is optimism, and it is a fact that this too has been vital to the survival of our species. It has wide ranging implications, but in this context it is in fact a cognitive bias that leads us to expect good from others, and, thanks to a variety of factors, most people maintain this view through life.

Following this thinking, the psychiatrist and neurologist Victor Frankl identified as a primary driver of human nature the quest for “meaning”. To give him all due acknowledgement, deference and respect, it is worth noting that his works are (at least in part) a consequence of his being a survivor of the Holocaust, having endured the brutal conditions of the Nazi death camps.

In his book “Man’s Search for Meaning” (2), in itself an autobiographical account of his experiences in several concentration camps including Auschwitz, we can see where his theory of “logotherapy” comes from. This includes the observation that individuals who were able to hold onto a sense of purpose and meaning in life were more likely to survive. Frankl proposed that even in the direst situations individuals could find meaning, thereby affirming their humanity.

3. It Helps us to Help

Another of the most influential psychologists of the last hundred years was Carl Rogers, and he highlighted that viewing humanity through a lens of inherent human goodness offers a number of potential advantages (3).

Looking at just one example (as long as we don’t dig too deep…) it offers us a route to compassionate understanding of negative behaviours: if we view them not as signs of inherent evil, but as the products of unmet needs or adaptation to challenging circumstances, it opens the door to empathy and understanding.

And it is true that this perspective can facilitate behaviour change practically, using approaches that underscore the value of nurturing capacities for empathy, cooperation, altruism, and moral reasoning.

However ...

… here is the problem I have found:

Despite having lived most of my life in a modern, peaceful and privileged environment, and despite the beautiful exceptions which unfortunately prove the rule, I have not been able to hide from the looming awareness that the evidence presented by humanity on the world stage – individually, in general, and throughout history – clearly shows the exact opposite!

So, in a spirit of intellectual and moral honesty (for those who are interested in such things), let’s explore just the possibility that humanity may not – in truth – be inherently good, and why denying this causes far more problems than it solves:

1. Define "Good"

Let’s start by getting some clarity on what we mean by “Good”, and thereby also its opposite, because a general woolliness seems to exist around what we mean by this concept.

Why do this? After all, surely we all know what “good” means?

Actually, no, we don’t – all we have done is assign a (suitably malleable) subjective humanistic definition that conveniently affirms who we are and what we do. It’s like asking a fish to define wetness.

The objective meaning of Goodness at the fundamental level is tied to the concept of Love. And by Love, we don’t mean the humanistic or romantic version, but the truest and purest version that defines Love – not just as unconditional – but as completely sacrificial of Self.

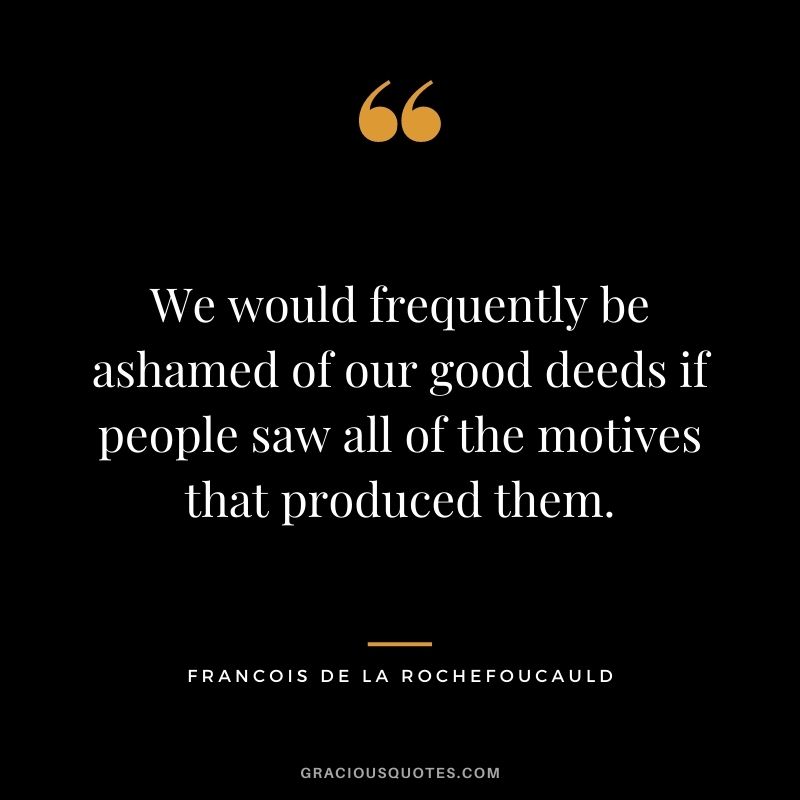

If we are going to compare to an objective standard, then the purest form of Love and Goodness can only be observed where there is:

- absolutely zero benefit, and

- a real absolute cost,

… to the person who is committing a truly Good act expressive of such Love.

Because only then can such an act potentially be labelled as truly and objectively “Good”.

2. Benefits and Costs

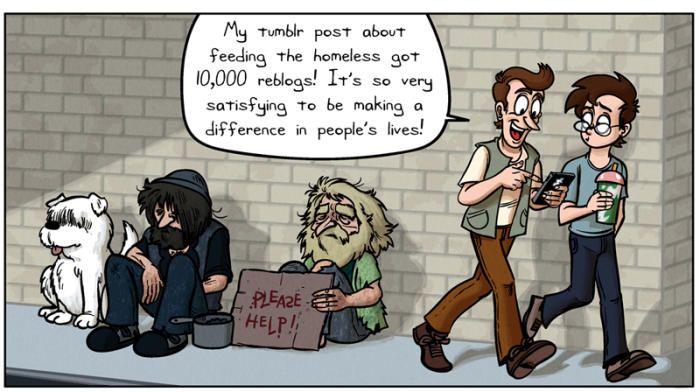

Therefore if, in any way at all, an act that would normally be labelled “good” has any underlying benefit for the individual committing the act, then it has the potential for having underlying selfish motives.

And we do instinctively know that selfish motives make an act “less good”.

In addition, no matter how extravagant an act of love may seem to the recipient, if it comes at little to no cost or sacrifice for the giver, how could the giver claim that a great deal of love is expressed in the giving?

Does it make a difference to the “goodness” of a gift of $10 if it comes from Bill Gates or from a poverty stricken widow? Of course it does! The need being met is almost irrelevant in an objective measure of how good the act is.

Consequently, we are volitionally fooling ourselves if we claim that any act that is either (let alone both) self-serving or low sacrifice, is actually “Good”.

And indeed we do: when we define an act as “Good” by measuring the benefit bestowed on the recipient, we are again being self-serving by using our subjective humanistic definition of what “Good” is!

As you can see, the difference between the objective absolute and subjective humanistic definitions is that we (very conveniently) like to define how “Good” an act is from the perspective of the beneficiary, whereas honesty and truth demand that absolute “Goodness” be defined with reference to the motives of, and benefits for, the Giver!

The fact that we don’t do this is a further indication of our collective nature. After all, as long as we can remove any dissenting voices, why would we make it harder to convince ourselves that we are in fact naturally good?

3. Is it Bad if I Serve Myself?

Which leads us to the definition of what is “not good” – any act that serves Self has, at the very least, the potential for being “not good”, and if in fact it does serve Self – even subliminally – then it cannot be labelled as fundamentally “Good”.

Furthermore, unless it is accompanied by real cost or sacrifice to Self, then the act by definition serves Self, even if only because it boosts our personal sense of righteousness, and much more so if the act is seen by others, thus signalling our virtue.

Does this mean that the act is “Evil” or “Bad”?

In and of itself – as far as the act is concerned – of course not. But more importantly:

… the serving of Self and the avoidance of cost to Self is a reflection of the underlying MOTIVE for the act. This motive in turn is a secretion of the underlying NATURE of the person who acted.

And so, by definition, it is this underlying Nature of the individual that can no longer be claimed as being naturally or fundamentally “Good”. In other words, even if someone has benefitted from an act of ours, if the act also served our Self, and at low relative cost to our Self, then a non-convenient and rigorous definition shows that we have not actually done something truly good, and even more so that our underlying motives and nature are actually anything but good.

In short, how can we claim to be “Good” by nature when everything we do – at some level – is actually self-serving?

So, having now defined what “Good” means in absolute terms, it is much less of a leap to claim that individuals are – and therefore that humanity in general is – NOT fundamentally Good, and that claiming that they are is in fact highly unrealistic and downright misleading.

We Can Prove It

No doubt you feel that this is a very bold claim, and because it is offensive to our natural mind you are probably inclined to find a way to reject it out of hand, as would a fish if told that air is better for travelling than water. But rather than debate the ins and outs of these claims and the definitions that go with them, let’s take a shortcut and return to a look at the evidence, shall we? We will do so on both a general and individual scale by asking ourselves a few simple questions:

Firstly, is the world we inhabit, both in aggregate and on average, getting better or worse? (Please note, this is just food for thought, and not an appeal to your social conscience).

If you are privileged enough to have a secure roof over your head and three square meals a day (or you are just generally not undernourished), then you are probably inclined to think that the world is getting better. After all, in your environment you probably don’t see much real poverty, and your and/or your friends’ children are at school rather than working in a coal mine. There are hospitals with doctors and nurses that wash their hands, day cares, homes for the elderly and infirm, shelters, social assistance programs, industries to help with mental and emotional issues. And if they get lonely, people today get pets to love, rather than to eat. There are wildlife sanctuaries, we grow gardens and designate areas of land to allow trees and nature to survive and thrive. Land reclamation projects. Wildlife protection programs.

Isn’t it awesome?

As is the fact that you have the education, the leisure time, and a device in hand to read this article.

Observe that You are Not Representative

If so, you are in the top sliver of the world’s population in terms of privilege, and you must admit that you have little to no experience of what the vast majority of people are dealing with every single day. Because that list above is something that this vast majority themselves have little to no experience of.

In fact, today – at a time when we in fact have more power collectively to actually make things better for everyone than ever before in history – we have a vastly greater gulf between those that have and those that have not than ever before in history, and so are signally failing to “become better”.

Again, this is NOT an appeal to your social conscience at all – it’s simply an appeal for you to look at a few facts, this being just one illustration designed to reveal a truth.

An extension of this thought is that most of us cannot see a critical lesson from history: in all likelihood, our privilege is fleeting, and either we or our descendants are going to experience poverty and suffering in the future.

Just ask the descendants of the nobility in Rome in the thousand years or so after its fall, or of any other wealthy society in human history.

So how on earth can we say things are better than ever?

We are wilfully fooling ourselves if we do, and the brainwashing Hollywood obsession with the basic goodness of Mankind is nothing more than a fairytale.

The point is simply this: if we measure suffering even purely anecdotally, things are not better at all, not on average and most certainly not in aggregate, and were you to take the time to observe the totality of suffering taking place right now you would realise that things are much much worse, and with less excuse, than ever before.

And what puts the final nail in the coffin of this “fundamental goodness of humanity” is the fact that only the tiniest minority of those that “have” – at any level and in any place and at any time – are anything but wilfully blind to the plight of those that “do not have”, even (if not especially!) those in plain sight.

If we could rely on the fundamental goodness of humanity, I must ask you:

where is the evidence?

A Study in Innocence

One last example by means of a few questions to illustrate why the fundamental goodness of humanity is nothing but an illusion:

Q1. When, in your opinion, would you say that a person is at his or her most innocent?

Most people’s answer is: as a newborn baby. Yes? That being said then:

Q2. When, in your opinion, would you say a person is at his or her most selfish?

Think about it. It’s the same answer, is it not?

Now, having read thus far, you may be experiencing a trace of cognitive dissonance (often expressing itself as a feeling of indignation), where your underlying belief system is at odds with the facts with which you are being presented. The reason is this:

->> We subjectively define a newborn baby’s innocence by virtue of the fact that he or she has done nothing wrong, and if we define innocence in terms of what a person has Done then it is indeed innocent. However, if we wish to identify the underlying Nature of the baby, then we see that this nature is not “Good” at all, because all newborn babies are 100% centred on Self and have zero regard for anyone other than Self, except insofar they can serve their needs.

You may say that this is obvious, even necessary for survival, and that is certainly true. But it does not change the fact that – when we use a rigorous, non-humanistic, objective definition of what it means to be “Good” – and despite its “cuteness” and lovability (to its mother at least) – the baby’s nature is anything BUT “Good”, because its NATURE is completely selfish.

Give a newborn baby the body of a college football player and he will murder his mother and wade through her blood to grab the shiny trinket that she has just denied giving to him. A creepy and freaky thought, but if you have ever experienced a baby throwing a tantrum then you should know it is true.

Paradise or Anarchy?

Ok, I lied about it being the last example (which just goes to prove the point). One more for you:

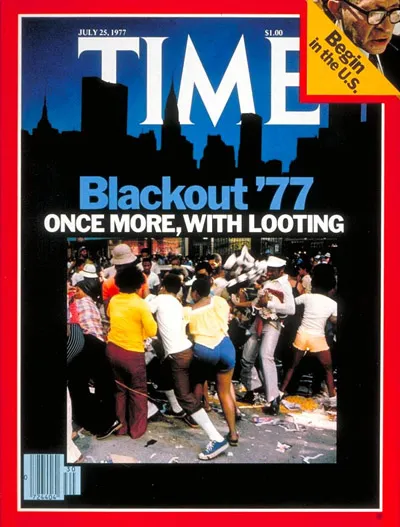

Q3. If, in your city, the power went out indefinitely and the authorities resigned their responsibilities and left, what would happen? And what would you do in response?

Oh wait, we have just seen that in the USA with the most privileged “poor” people in history, and the power didn’t even go out!

Or what about when people interact anonymously or can do so without consequence, such as on social media: do you see kindness and goodness prevailing generally, or do you see vitriol and hatefulness?

Need I say more?

You may say that this is obvious, even necessary for survival, and that is certainly true. But it does not change the fact that – when we use a rigorous, non-humanistic, objective definition of what it means to be “Good” – and despite its “cuteness” and lovability (to its mother at least) – the baby’s nature is anything BUT “Good”, because its NATURE is completely selfish.

Give a newborn baby the body of a college football player and he will murder his mother and wade through her blood to grab the shiny trinket that she has just denied giving to him. A creepy and freaky thought, but if you have ever experienced a baby throwing a tantrum then you should know it is true.

Goals Revisited

In conclusion, when we revisit our illustrative draft goals for humanity above, we are forced to be honest:

- The goal is to improve the lives of people – but for sure I’m starting with myself, and in any case I’m not sacrificing my own lifestyle, let alone my life – and if I can get someone else to pay for it then so much the better;

- Let’s live in peace and abolish war – well yes, because war is unpleasant for everyone at some level, including ourselves, but if it’s in some far flung corner of the world where our tax dollars are not involved then so much the better;

- The triumph of humanity would be a society where everyone is fundamentally happy – best then to start with myself; after all, not everyone will be happy if – first and foremost – I myself am not happy!

So I’m doing my bit. What about you?

My guess is: working on the same as me, and exercising your right to pursuing your happiness.

There are some expansions on our discussion that space denies me from including in the article and that I have included in the notes below, including responses to both Frankl and Rogers, a look at the beliefs of that beautiful soul Anne Frank, and an examination of the exception of altruism (spoiler alert – it’s not an exception), but for anyone who is interested in understanding the truth of who we are, collectively and individually, a rigorous examination of what it truly means to be truly Good forces us to admit that we are in fact our own worst enemy.

And the cost of not doing so is this: by living in (at best) blissful ignorance and (at worst) denial, we in turn deny ourselves the opportunity of being able to do anything about it.

Speaking of which, if you are interested in how it is possible for each one of us to crawl out of this comfortable sewer we live in and truly make a difference, please check out our other articles.

References

1. Mafessoni, F., Lachmann, M. The complexity of understanding others as the evolutionary origin of empathy and emotional contagion. Sci Rep 9, 5794 (2019).

2. Frankl, Viktor E. (Viktor Emil), 1905-1997, author. Man’s Search for Meaning : an Introduction to Logotherapy. Boston :Beacon Press, 1962.

3. Carl Rogers: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Rogers

Notes

Note 1: Altruism

This human attribute has often been presented in defence of mankind’s instinct towards goodness. We have many extreme examples of personal heroism, celebrated especially in times of war where both the “best” and the worst of human nature are visible, but it can also be observed in many areas of human existence.

However, the bald fact of the matter is that, where it truly is altruism and nothing else, it is almost exclusively generated by empathy, and empathy by definition means that the subject identifies with the Object of their empathy. In other words, the person being altruistic unconsciously sees themselves in the object of their altruism. (See reference (1) above).

Can you see the underlying implications of this?

This common identity is often true at a group level, where it is not uncommon in history to see an individual sacrificing themselves for the benefit of their group. In this case, what we see is the person finding their identity almost completely in the identity of the group, and therefore the priorities of the group become the priorities of the individual, all the way to matters of life and death.

Now, much as we can admire this, and as human beings we almost inevitably do, if we are interested in an act of altruism being fundamentally good we need to subject it to our rigorous and objective definition of what it means to be “Good”.

In the second criterion identified in the article, we can certainly claim that there is a real cost involved to the individual, up to and including the individual sacrificing their life. However, as the identity of the individual (“Self”) is now merged – in their own mind and collectively – with the identity of the group, even the individual will see the cost of sacrificing their own life as less important than the benefit or gain for the group. Therefore, the net cost to the group “Self” is perceived as – at least relatively – low, compared to the net benefit, when sacrifice of the individual is called for.

Which brings us to the first criterion of underlying benefit: certainly there is a benefit – most obviously for the group – and so the individual’s act of altruism now becomes one of serving the revised “Self” – this being the interests and identity of the group. In addition, because of group dynamics, the individual knows that they will be regarded forever in the collective memory of the group as a “Hero” – and so in fact they still serve “Self” even at the individual level.

As a social species, this is without question one of the reasons our species has survived – the ability of individuals to sacrifice themselves for the greater “good” is a massive survival advantage for the species as a whole (Richard Dawkins’ book “The Selfish Gene” hypothesises on how deep this goes)(5).

However, if by “good” we simply mean the survival of the group then fine, but not when we demand a more rigorous, non-humanistic definition of “Good”, greater or otherwise.

A reductive illustration would be someone with their foot caught in a bear trap with no hope of rescue, knowing that unless they cut off their foot they will certainly die. Brave, and to be admired, certainly! And not everyone will be able to do it and thus survive.

But is it a fundamentally good act, or a self serving one?

In short, when we associate our “Self” with someone else, be it an individual or a group, we release the capacity for empathy. This is undoubtedly beneficial to the recipient and even to survival of a group, society and the species, but do the resulting actions qualify for being fundamentally good?

Only if we define “good” in a humanistic and self-serving way.

(And in any case: in what way has the survival of humanity been a “good thing”? If we consider our survival good simply for its own sake, then an objective observer could say the same thing for cockroaches.)

Note 2: An exception? Anne Frank

I clearly recall reading The Diary of Anne Frank as a junior in high school because it was one of our prescribed setworks. And thank goodness I did get to read it at a young and formative age, because it is a wonderfully inspiring albeit tragic account of the triumph of the human spirit!

In case you don’t know about her (and to quote a great summary)(4):

“Anne Frank was a Jewish teenager who lived with her family in hiding from the Nazi regime, and gained fame through the publication of her diary after the war. The Frank family moved to Amsterdam in 1934 to escape the escalating persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany. However, following the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, they went into hiding in a secret annex in her father’s office building. Anne, her sister Margot, and their parents lived in this clandestine space with four other Jews until 1944, when they were discovered and transported to concentration camps. Anne and her sister died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen camp in 1945. Anne’s father, Otto Frank, the only survivor of the family, later published Anne’s diary entries, providing the world with a poignant glimpse into her life in hiding.”

Anne’s statement “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart,” comes from one of her diary entries written on July 15, 1944. This was less than a month before they were discovered and arrested.

Now, to those of us who are inspired by her writing, her quote reveals a resilient optimism and belief in human goodness, even as she faced severe oppression and lived in constant fear for her life. But psychologists take it further: they believe that her diary reveals “an unwavering hope that underlines a human capacity for goodness, irrespective of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis” (4).

How could we disagree with that?

Well, if we try to extract ourselves from our natural tendency towards sympathy and look to be truly objective, there is something to note here:

->> Anne’s belief “that people are truly good at heart” shows us that the attributes of hope and courage and resilient optimism are not necessarily based on the truth of the matter, but are in themselves sometimes necessary for survival. As such, her quote is not only a statement of belief, but also a testament to the power of optimism, hope, and belief as an advantage in surviving overwhelming adversity. However, that power is still being exercised towards benefiting Self, be it as an individual or a group.

That being said, we as humans must still appreciate the qualities that Anne displayed, and as humans we must value the people who do display them. I have nothing but incredible admiration for her and others like her, and I doubt very much that I would do as well, despite the inspirational example she set for us to follow.

In any event, once again the objective historical evidence in the form of Anne’s (and 11 million other Holocaust victims’) personal experience shows that her belief “that people are truly good at heart” was wrong. I often wonder what she would have written after experiencing the Nazi death camp, which of course leads us to …

Note 3: Response to Victor Frankl

My (real and very strong) sympathy for Holocaust survivors might be evident here because I am quoting another person who was a victim of the Holocaust, but in fact this is purely coincidental. What might be more interesting is to wonder if such a terrible experience created similar views on topics such as the fundamental goodness of humanity. Certainly we can safely assume as a start that most people who are exposed to the worst our fellow man can do would think deeply about this question.

What is more interesting and even startling is that their conclusion was equally in favour of the fundamental goodness of mankind! This in itself is a remarkable testament to the natural disposition of people towards optimism, hope and belief. (Please note however that this similarity in outlook is due to a selection bias – after all, we are not writing about the many people who did in fact come away with intense disillusionment).

In his experience, Frankl observed that those who were able to hold onto a sense of purpose and meaning in life were more likely to survive. Despite witnessing some of the most despicable acts of human cruelty, he maintained a belief in the possibility of human goodness. Frankl proposed that even in the most dire situations, individuals could choose their attitudes and find meaning, thereby affirming their “humanity”.

There is a lot more to it but the essential gist of it is encompassed in that brief precis, and as with Anne there are some things to note here:

- His observation of choice is limited to the choices available, and when you are fighting for survival your choice is fundamentally limited to finding meaning or finding disillusionment. In his own words therefore, finding “meaning” in adversity is simply another survival technique.

- When it comes to those who had a wider set of choices available to them, including that of “meaning”, in the case of his Nazi captors we do not see a choice being made in favour of a search for meaning at all. The wider set of choices for the captors included the freedom to indulge in the worst that human nature can produce, or not to do so. This extends beyond the SS soldiers in the camps to the citizens of the land, including doctors, nurses, school teachers and even children.

In other words, when human nature is freed from restraint, be it an enforced legal system, or moral upbringing, or religion, or any other programmed moral restraint, the historical evidence of who we are naturally at the deepest level is clear.

No matter how much we want to believe otherwise, or what our humanistic culture teaches us.

->> Once again, if you can see the truth in this and want to know what to do about it, look at our other articles and be sure to follow the Page.

Note 4: Response to Carl Rogers

Born in 1902, Rogers is without question one of the most influential psychologists of the last hundred years or so, and was also one of the founding figures of the theory of “Humanistic Psychology”.

The core of this theory is the “actualizing tendency”, the innate drive in all organisms to grow, change, and strive towards fulfilment and the release of their positive potential. Rogers believed that “every person is like a seed with the innate potential to grow and flourish into a vibrant, unique, and robust plant. This inherent capacity for growth and self-actualization is the natural state, much like a seed instinctively knows how to germinate, to push its sprouts towards the sun, and to unfurl its leaves for photosynthesis.” (4)

He continues: “the ‘actualizing tendency’ can be likened to the inherent genetic blueprint within the seed, guiding its growth and development. This blueprint nudges the seed towards becoming the best version of the plant it is meant to be.”

However, he acknowledges that – and this is where we see the problem beginning to show – every seed also needs to have a healthy environment conducive to helping it flourish rather than struggle and wither into something ugly. In other words, if we are going to blame anyone or anything for the general failure of individuals to flourish and become the best version of themselves, we need to blame the environment.

Sound familiar?

The obvious question then – for me anyway – is this: what do you think the environment is made up of? It’s not a different element, like soil or sunshine is to a seed. It’s other people! Each one of which is supposed to possess this same “actualizing tendency”!

Therefore, if there was a grain (or is it a seed?) of truth to this theory, then clearly the collective natural tendency of society would be to follow the natural tendency of the individuals in an inevitable culmination of being the best we can be, and without needing any (or at most very limited) enforcement. And of course this is what some people believe is happening, BUT, is there any real empirical evidence to support this?

I mean, beyond our bubbles of privilege, any AT ALL?

The answer is of course a resounding NO because, without real enforcement, what we see is an inevitable tendency towards anarchy and chaos, and the worst that mankind has to offer. Without forms of external restraint, be it an (enforced) legal system, or a moral upbringing, or religion, or any other programmed moral restraint, or preferably an effective combination of all of these, the historical evidence of the natural outcome is again clear. The fact that even these tend to corruption simply further proves the point that whatever man touches he corrupts.

That being said, I think we all can – and should! – get behind many of Rogers’ conclusions, including “helping individuals recognise their innate capacities for empathy, cooperation, and altruism”, or nurturing qualities such as “resilience, creativity, and ethical reasoning”. However, we do not need an unrealistic (and flawed) model to know that this is the right thing to do, and under no circumstances should we rely on our imagined collective natural tendency to do so.

Because, as much as we can admire Rogers’ optimism (there is that survival bias rearing its head again), and I sincerely do, the evidence shows that this optimism is unfortunately divorced from reality.

Most concerning is that he suggests a reliance on an institutional approach to fostering these initiatives, which once again speaks to the creation and maintenance of the “environment” by other people who are by (his) definition fundamentally good and who possess this “actualizing tendency” towards goodness!

And this is precisely the model that – at least in many developed countries – has been followed now for many decades.

Which means that, if we look at the effectiveness of these institutions today, from government to schooling to law enforcement to the judicial system, where the actors are there exclusively to serve the needs of others, we should see a general improvement in both general behaviour and in our environment, should we not?

Once again, much as we love to live in denial, the evidence speaks for itself.

Further References

4. Steve Rose (PhD): https://steverosephd.com/why-i-believe-humans-are-inherently-good/

5. Dawkins, R. (2006). The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press.